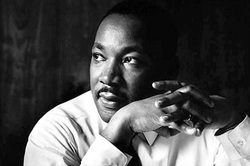

Remembering Dr. King's housing legacy

In honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the Latino Policy Forum—a leading voice in housing issues in the Chicago Metropolitan region—pays tribute to the life and important work of Dr. King, especially in the fair housing arena. The Forum's Housing Manager Savannah Clement sat down with Communications Associate Emily Vasquez to reflect on the many ways Dr. King's legacy still inspires fair housing advocates almost 50 years later.

Q: What was Dr. King's housing legacy? How does it still resonate today?

A. It is well known that between the mid-1950s until his assassination in 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. played a pivotal role in the civil rights movement. He was a proponent of non-violence, and carried out his civil rights agenda through peaceful protests such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington in which he gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

What may be lesser known, however, is that Dr. King was also the driving force behind laws that protect equal rights in housing in the United States. He advocated for integration and better living conditions in low-income communities. Locally, between 1965-1967, Dr. King led the Chicago Freedom Movement, also known as the Chicago Open Housing Movement—which included a series of demonstrations that raised awareness and demanded change for housing segregation and discrimination. Dr. King's death in 1968 became a catalyst for fair housing legislation, causing President Lyndon B. Johnson to push the Civil Rights Act of 1968, along with Title VIII, through Congress and sign it a week after the assassination.

Title VIII which is best known as the Fair Housing Act aimed to expand protections against discrimination based on race, color, national origin, and religion in the sale or rental of housing. In an attempt to commemorate Martin Luther King Jr. and his work to end residential segregation, Congress made housing discrimination illegal and paved the way for housing advocates—like the Forum and its Housing Acuerdo—to continue Dr. King's work by promoting equal access to housing for all.

Q. What were some challenges Dr. King faced in his time? What are some challenges housing advocates face today?

A. In the 1960s, Chicago was one of the most segregated cities in the country. This was in part due to the federal government-sponsored Home Owner’s Loan Corporation and its maps of American communities that rated and ranked which ones were suitable for lending. This process was called “redlining” because communities of color were outlined in red and deemed undesirable for loans. Many banks and lenders used these maps to determine which neighborhoods were eligible for loans, and if redlined, which neighborhoods were not. Because of redlining, communities of color were cut off from capital and the possibility of acquiring wealth via homeownership. Redlining was a huge contributor to the segregation of Chicago’s neighborhoods.

When Dr. King began his housing work in Chicago, he faced enormous backlash and resistance from the residents of Chicago. During one demonstration in Marquette Park, protesters were screamed at, and had stones, bottles, and firecrackers thrown at them. 30 people sustained injuries including Dr. King. After the protest, Dr. King acknowledged that Chicago was different than other places he’d worked by saying, “I have seen many demonstrations in the South, but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today.”

Today, Chicago still experiences housing segregation and the effects it has on communities of color. While discrimination has become less overt and more discreet, it is still prevalent in Chicago housing. Additionally, redlining has become more covert but there is still evidence of its existence. One staggering example: the foreclosure crisis. Communities of color were largely targeted by lenders for subprime predatory loans, regardless of creditworthiness. Many people who received these loans were not able to make the payments due to changes in loan terms and/or a reduction of income due to the recession. Consequently, many people of color lost their homes, and by extension a substantial amount of wealth, during this crisis. The effects of the crisis can still be seen in the city’s south and west side neighborhoods where houses continue to stand vacant and boarded up.

Q. What have been some positive outcomes due to the fair housing act and other acts passed?

A. In Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs vs. Inclusive Communities Project, the Supreme Court upheld and affirmed disparate impact in fair housing discrimination claims. This ruling allows people to file a claim against an entity that may have a facially neutral non-discriminatory policy that has a disparate impact, or discriminatory effect, on a protected class of people. In other words, there does not need to be any discriminatory intent behind the policy. It only needs to be proven that the policy negatively impacts a certain group of people that are protected under the Fair Housing Act. This is significant for housing advocates as it provides a tool for combatting discrimination that is less obvious.

Additionally, the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (“HUD”) instituted a new Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing Rule (AFFH). This rule aims to promote housing integration and strengthens previous efforts to affirmatively further fair housing. This could allow housing advocates to push for new policies that stimulate housing integration in the years to come.

Q. What is the state of fair housing today? What role does the Forum play?

As previously discussed, Chicago is still one of the most segregated cities in the U.S., and discrimination remains alive in its housing market. However, it should be noted that despite these challenges, Chicago has a very strong and inclusive Fair Housing Ordinance. It expands on the protected classes provided by the federal Fair Housing Act by ensuring protections from discrimination for people based on their race, national origin, familial status, disability, sexual orientation identity, source of income, religion, gender or gender identity, age, marital status, military status, and the status of any domestic violence order of protection.

As a city, we've come a long way in combatting housing discrimination, but we still have many miles to go. Fair housing is about choice and having the freedom to choose where you want to live without discrimination. The fair housing journey will not end until everyone truly has that ability.

The Forum does not work alone in its pursuit for fair and equitable housing opportunities. It partners with many great groups around the Chicago area that are doing meaningful fair housing work, through its Housing Acuerdo. Some examples are the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance (CAFHA), the John Marshall Law School Fair Housing Legal Clinic, and the Latin United Community Housing Association (LUCHA), to name a few.

The Forum also recognizes the month of April as Fair Housing Month, and uses this opportunity to provide housing resources to the community though outreach and education with our partners. In 2015, the Forum collaborated with Chicago’s Mexican Consulate and 15 local organizations to reach more than 3,700 community members throughout the month and connect them to resources, workshops and information about federal, state and local housing ordinances.

For more information on the Housing Acuerdo, or about the Forum's housing goals and strategies feel free to drop me a line at sclement@latinopolicyforum.org.